Case 30

This 86-year-old woman with a long-standing history of hypertension, COPD, anemia, and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) was brought to the emergency department complaining of SOB

This 30-year-old woman complained of having had about ten episodes of syncope associated with mild exertion for the past six months. During physical activities, she also experienced intermittent dizziness, shortness of breath, chest pain/tightness, palpitation, and cold sweating. PMH was significant for G6, P2, s/p appendectomy, and chronic hepatitis C. Family history was unremarkable. ECG tracings showed RA and RV enlargement, RV strain, and clockwise rotation evolved over three years. She had moderate respiratory distress (BT= 36.°4C, PR 120/min, RR 20 /min, BP 109/74 mmHg). Lungs were clear, RV lift was palpable, and there was JVD with JVP 10 cm H2O. S2 intensity was notably increased at the pulmonic area, and a Gr 2/6 TR murmur (increased in intensity during inspiration) was heard at the left lower sternal border. Laboratory data were within normal limits: Hb14.1 gm/dL, WBC 7,790 /uL, GOT 28U/L, GPT 35 U/L, D-dimer 115 (N <500) ng/mL, FDP <0.2 (N <10) ug/mL, protein S 34.5 (N >60) %, protein C 98.5 (N 70-140) % and anti-thrombin 3 62.9 (>75) %, ANA 40x- (N <40x-), DNA Ab – at 10x, anti-SSA/Ro 57 (N <120) AU/mL, anti-SSB/La 92 (N <120) AU/mL, VDRL 12x reactive (N nonreactive), HIV negative, RF 21.9 (N <20), Anti-cardiolipin IgG 5.8 (N<15) GPL, Anti-cardiolipin IgM 5.2 (N <12.5) MPL, Free T4 1.28 (N 0.89-1.76) ng/dL and TSH 1.39 (N 0.40-4.0) uU/mL. Spirometry showed that FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and FVC are within the normal predicted values (98%, 93%, and 105%, respectively). Echocardiograms showed markedly dilated RA and RV, severe TR with RV systolic pressure (RVSP) 89 mmHg, and normal LV wall motion with LV EF 60%. CT angiography revealed no definite filling defects within the pulmonary trunk, bilateral PA, and their branches. Although pulmonary angiography would be more definitive, it wasn’t done. Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension was deemed the most likely diagnosis, and the patient was considered a functional class 3-4 because of recurrent syncopal episodes on mild exertion

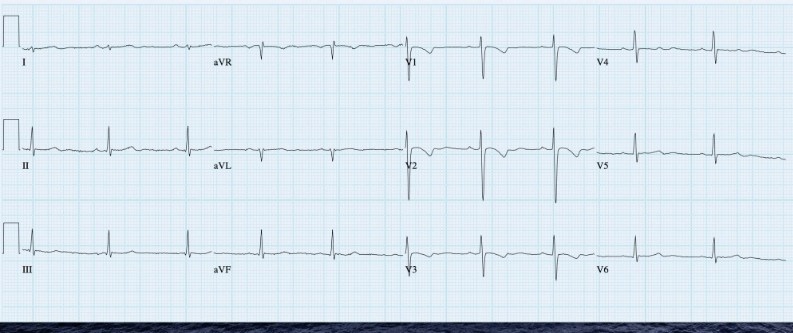

Sinus tachycardia at 128/min

Right axis deviation (+123°) and slow R progression in V1-V6 (vertical heart; clockwise rotation), a form RV enlargement

Tall P in II, III, and aVF c/w RA enlargement (Cor pulmonale) suggesting pulmonary hypertension.

T inversion in II, III, and aVF and V1-V4 representative of RV strain in a clockwise rotated heart

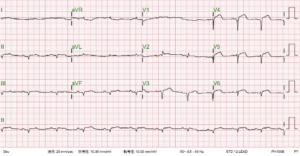

Sinus rhythm at 60/min

Borderline right axis (+90°)

T inversion in V1-V3 suggestive of RV strain

Note normal P waves compared to the one taken on admission

Prominent bilateral PA segments indicative of pulmonary hypertension.

Vertical heart

The lateral view (the view to illustrate RVH) was not obtained.

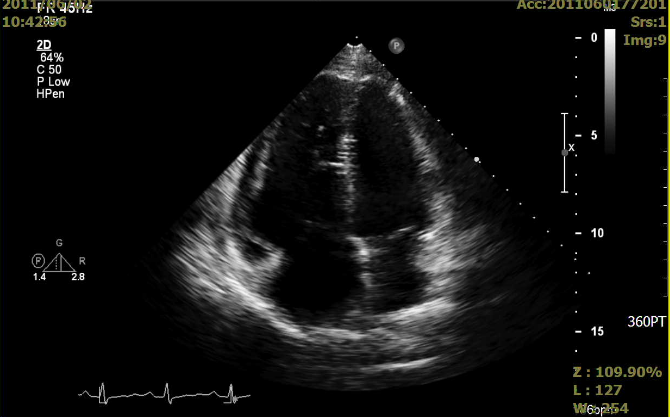

Markedly dilated RA and RV

Moderate pulmonary regurgitation, severe TR with RV systolic pressure (RVSP) measured 89 mmHg

Normal global LV systolic function and no regional wall motion abnormality, LV EF: 60%.

No filling defects were noted within the pulmonary trunk, bilateral PA, and their branches.

No evidence of lymphadenopathy

ECGs, chest x-ray, and echocardiographic findings point to the diagnosis of chronic PH. In a strict sense, the ECG term “Cor pulmonale” is used to describe RA enlargement caused by diseases of the lung (e.g., COPD), vasculature (e.g., idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension), airway (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea), and chest wall (e.g., kyphoscoliosis). Regarding RA enlargement due to other etiologies, such as left-sided HF and congenital heart diseases, “Cor pulmonale” should not be used.

The etiology of chronic PH, based on the underlying pathophysiological mechanism, can be classified into five groups:

In the present case, CT pulmonary angiography and serial blood tests, including cardiolipin antibodies, have excluded chronic pulmonary thromboembolism and autoimmune disorders (e.g., syphilis, antiphospholipid syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus). Understandably, there are also unclear multifactorial mechanisms that can cause PH. Pulmonary arterial hypertension is rare in which lung blood vessels become progressively constricted and narrowed. The resultant pressure elevation in the pulmonary arteries forces the RV to work harder to pump blood to the lungs, leading to RV enlargement and right-sided HF. Notably, idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension can be familial or sporadic without a family history.

In general, PH can lead to dyspnea on exertion initially and eventually while at rest, fatigue, dizziness or fainting spells (syncope), chest pain or tightness, leg edema, liver congestion (hepatomegaly), ascites, cyanosis, palpitations, and even sudden death. Fortunately, considerable advances have been made in the pharmacotherapy of PH (e.g., endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, sGC stimulators, prostacyclins or analogs, etc.).

Because the underlying pathophysiological mechanism varies, the treatment strategy is according to the cause of PH. For example, optimal control of HF (left-sided and right-sided) is essential in patients with PH due to left heart disease. Some group 1 patients (i.e., idiopathic, heritable, and drug/toxin-induced) may first undergo an acute vasoreactivity test to see if they would respond to calcium channel blocker therapy (about 10-20 %) before needing other medications. In contrast, the vasoreactivity test is not indicated in patients with associated forms of pulmonary arterial hypertension (e.g., connective tissue disease, congenital heart disease, HIV, portal hypertension, etc.) as they are rarely vasoreactive. Furthermore, specific therapy for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension is not beneficial in most other forms of PH and may even be harmful. Lastly, primary care physicians should know that many PH expert care centers are available for referrals.

Keywords:

chronic pulmonary thromboembolism, pulmonary angiography, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), pulmonary hypertension (PH)

UpToDate:

Clinical features and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension of unclear etiology in Adults

Treatment and prognosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults (group 1)

This 86-year-old woman with a long-standing history of hypertension, COPD, anemia, and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) was brought to the emergency department complaining of SOB

This 69-year-old man had been in good health until two days before admission when he returned from a beach. He experienced general weakness with chest

An 88-year-old woman complained of a loss of appetite, generalized weakness for two weeks, and increasing SOB for five days. She had chronic heart failure

If you have further questions or have interesting ECGs that you would like to share with us, please email me.

©Ruey J. Sung, All Rights Reserved. Designed By 青澄設計 Greencle Design.