Case 9

A 67-year-old woman experienced progressive dyspnea with PND and leg edema for two weeks. PMH was significant for chronic hypertension for 20 years.

This 50-year-old man came to the Emergency Department complaining of having substernal chest pain for more than 10 hours. The pain was sharp and not exertion-related. It could radiate to the left shoulder, back, and scapula. It seemed positional, as inspiration could worsen it, and leaning forward could somewhat mitigate the pain. At times, he also experienced nausea, dyspnea, and cold sweats. Reportedly, he had flu-like symptoms with a runny nose and sore throat but didn’t visit any clinic seeking help. Past medical history was significant for thalassemia, mild GERD, and gallbladder stone diagnosed ten years ago. He looked apprehensive due to chest pain, but he was alert. BT/PR/RR measured 37 ℃ /86 /min/14/min, and blood pressure was 123/66 mmHg. There was no JVD or leg edema. PMI was in the mid-clavicular line at the left 4th/5th intercostal space. There were no murmurs, but both systolic and diastolic friction rubs and bilateral basilar crackles were audible. The rest of the physical findings were unremarkable. ECG showed sinus rhythm at 72/min. Notably, there was diffuse ST segment elevation in all leads except for aVR with P-R segment depression in inferior and anterior chest leads; also, there was a QS pattern in leads V1 and V2 suggestive of old antero-septal MI. The chest X-ray revealed slight cardiomegaly, torturous aorta, increased lung infiltrates at the right lower and left middle lung field, and prominent hilum on the right side, suggesting an infectious process. Pertinent laboratory data include Hb 12.5 g/dl, Hct 39.1 %, WBC 8.89 x10^3/ul (baso 0.1 %, eos 1.1 %, lym 9.1 %, mono 7.2 %, neut 82.5 %), Plt 215 x10^3/ul, BUN 9 mg/dl, Cr 0.72 mg/dl, glucose 132 mg/dl, Na 138 mmol/l, K 4.0 mmol/l, GOT 22 U/l, CK 59 U/l, CK-MB 1.4 ng/ml, troponin I 0.01 ng/ml. Two hours later, his symptoms persisted, and cardiac enzymes showed a slight increase in troponin I 0.05 ng/ml. ECG showed diminished voltage in precordial leads and Q waves in V1-V3. To rule out coronary syndrome (ACS), the care team did an emergency cardiac catheterization with coronary angiography, which revealed all arteries were patent. A subsequent chest CT scan also excluded aortic dissection. Still, it disclosed mild calcification over coronary arteries and aorta, pericardial thickening with mild pericardial effusion, and a small amount of bilateral pleural effusion. He then developed a low-grade fever (37.6-38.2℃). The corresponding CRP measured 23.1, ESR 16, and WBC 11.17. The echocardiography revealed slight concentric LV hypertrophy with an EF of 71% and a small pericardial effusion. The care team empirically started levofloxacin to combat possible bacterial infection. RA factor was normal, and so were Weil-Felis (rickettsia infection) and Widal (typhoid and paratyphoid) tests. With supportive therapy, the rest of the clinical course went uneventfully, and he could return home in two weeks. Before discharge, the care team had given him a schedule of follow-up plans.

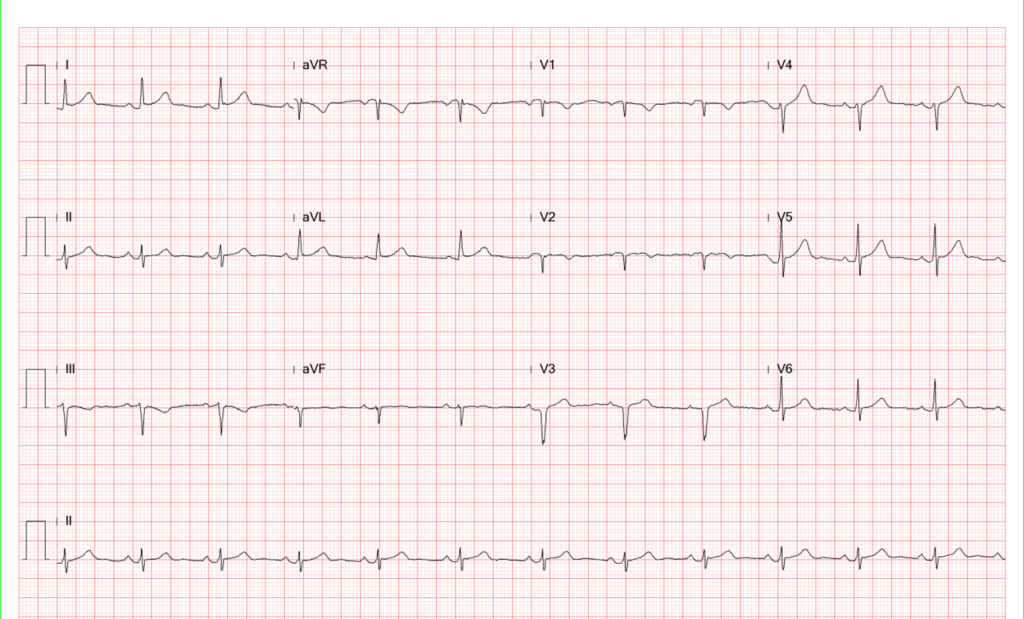

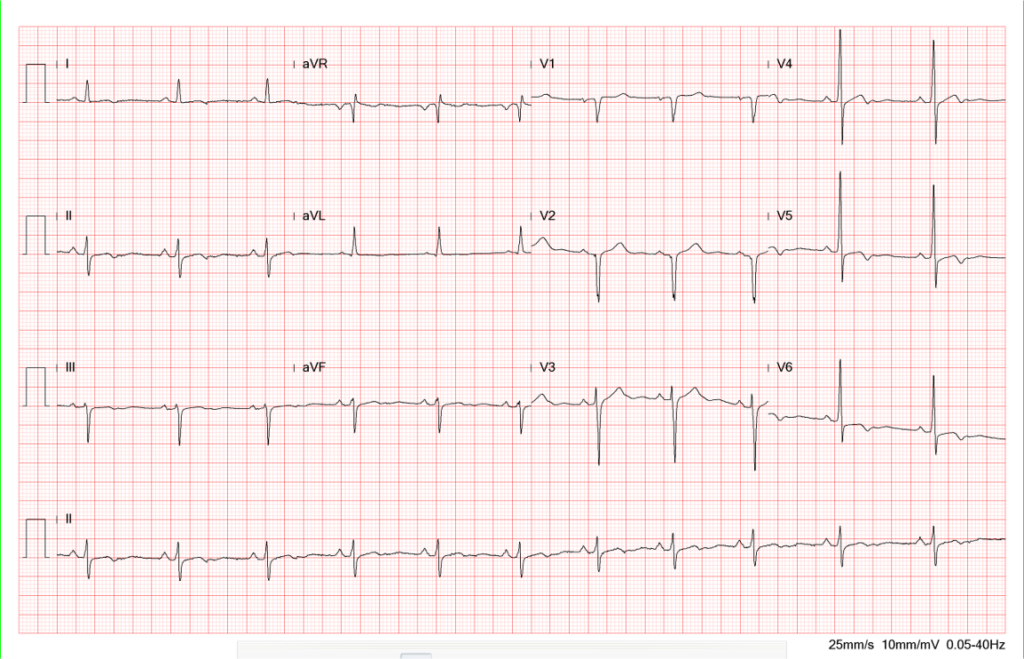

Sinus rhythm at 72/min

Diffuse ST segment elevation in all leads except for aVR

P-R segment depression in inferior and anterior leads

QS pattern in leads V1 and V2 suggestive of old antero-septal MI.

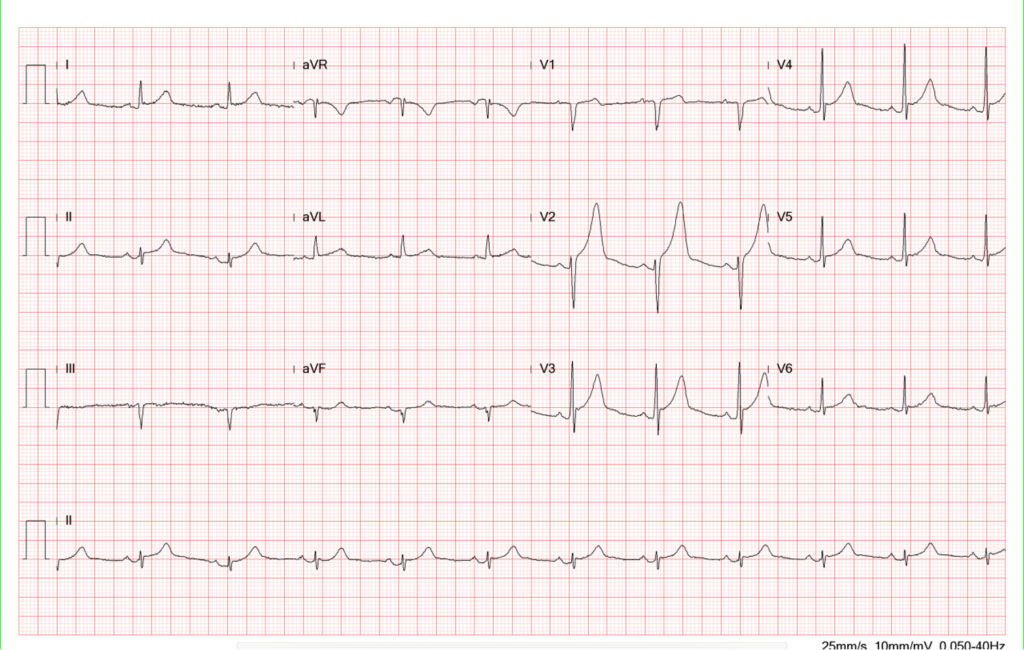

Compared to the previous tracing, there is a significant decrease in the QRS amplitude especially in the precordial leads.

Q wave in V1-V3 suggestive of an old anteroseptal MI.

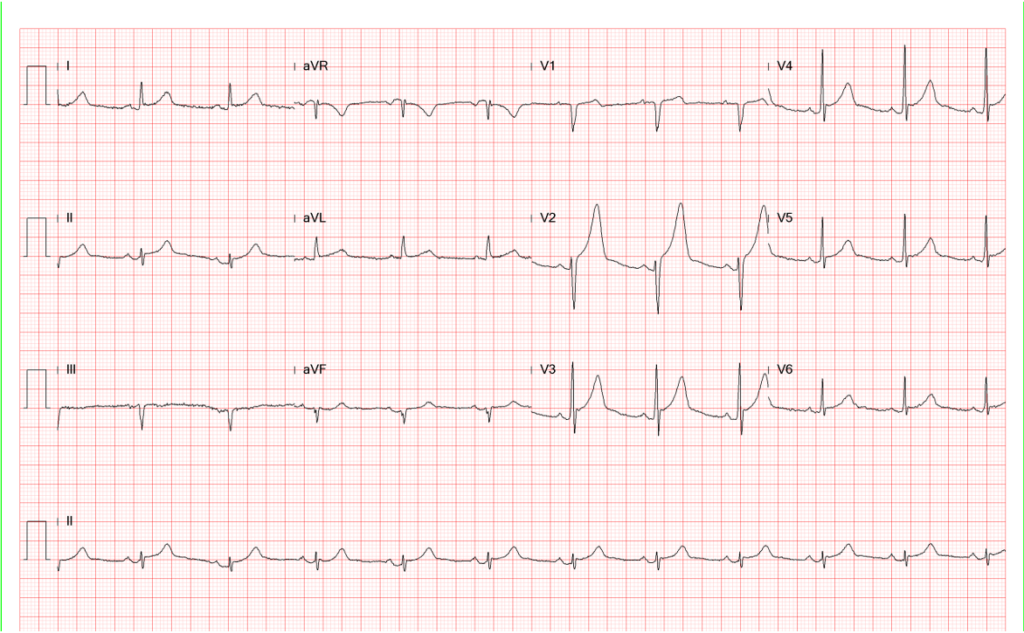

Compared to previous tracing, the QRS complex has regained its amplitude.

Compared to the previous tracing, some shifting of ST-T changes in the precordial leads.

There is significant decline in ST-segment elevation and the T wave amplitude.

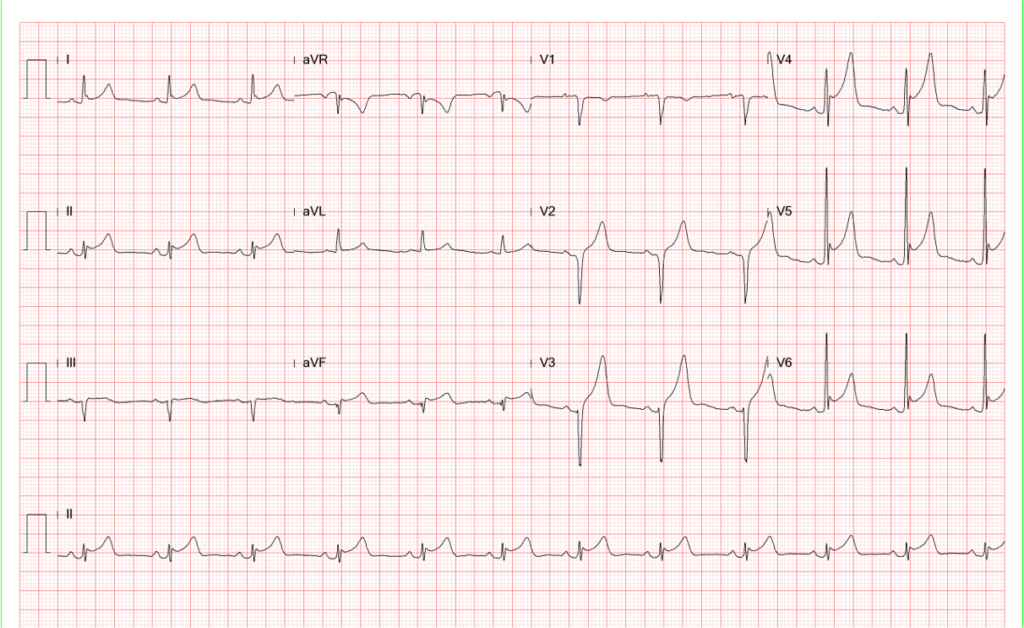

ST-segment elevation is no longer visible, and there is T wave inversion in leads I and V4-V6.

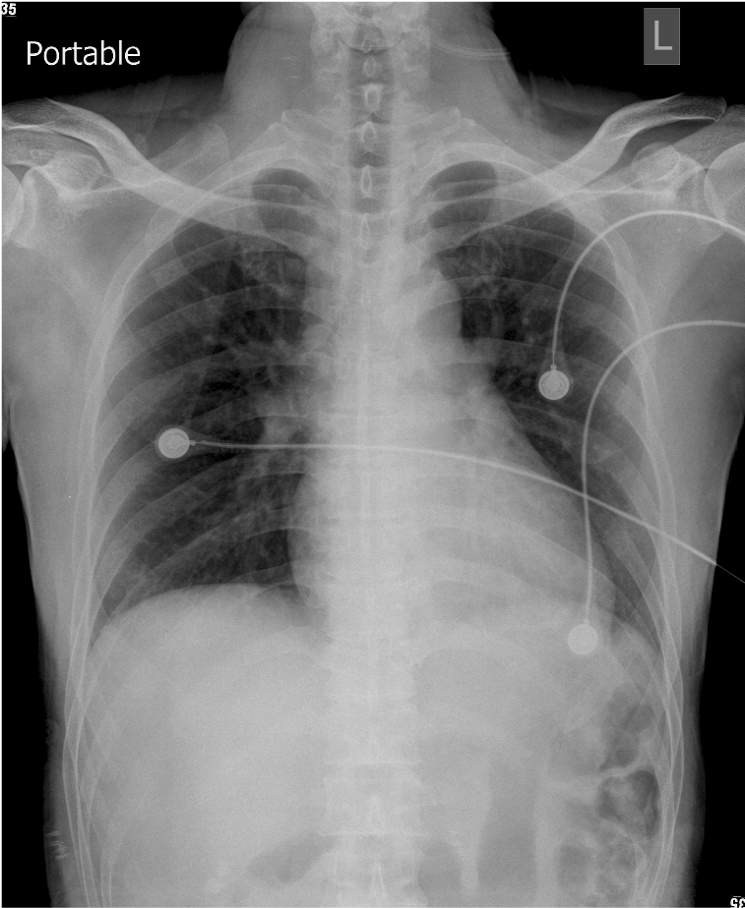

Slight increase in the cardiothoracic ratio

Torturous aorta

Widening of right paratracheal stripe

Prominent vascular structure or right paratracheal lymph node or focal lesion

Increased lung infiltrates at the right lower and left middle lung field.

Prominent hilum on the right side suggesting an infectious process

Acute pericarditis is diagnosed through clinical assessment (e.g., history and physical findings), laboratory testing, and imaging studies. The chest pain in pericarditis is typically positional and worse when lying flat, easing up when sitting forward. Signs of pericarditis may include pericardial rub heard on auscultation. However, transmural myocardial infarction, STEMI (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction), may also develop related pericarditis (Dressler’s syndrome) with low-grade fever and pericardial friction rubs.

Acute pericarditis can involve the myocardium, causing myopericarditis, which may lead to some elevation of cardiac enzymes. ECG findings suggest acute pericarditis, including widespread concave ST elevation and P-R segment depression occurring throughout most limb leads (I, II, III, aVL, aVF) and precordial leads (V2-6). The widespread upward concave ST-segment elevations can mimic STEMI, like the present case. In STEMI, the ST segment elevation is usually convex in contour. The degree of ST elevation in acute pericarditis is typically modest (around 0.5-1.0 mm), and reciprocal ST depression and P-R segment elevation are often seen in lead aVR (and sometimes V1). Sinus tachycardia may be seen with pain. Based on ECG evolutionary changes, there are four stages, some of which are illustrated in the present case (ECGs 1-5):

Stage 1: Widespread concave ST elevation* and P-R depression with reciprocal changes in aVR.

Stage 2: Normalization of ST changes; general T-wave flattening

Stage 3: Flattened T waves become inverted

Stage 4: ECG returns to normal

However, the evolutionary changes may take several weeks, and not all patients progress through all four stages.

Other clinically pertinent ECG features associated with pericarditis include low voltage across all leads due to pericardial infusion, which causes an increased resistance for signal transmission (e.g., ECG 2), and electrical alternans, in which there is beat-to-beat alternation in QRS complex amplitude due to the swinging of the heart in a large pericardial effusion. Pathological Q waves suggesting prior myocardial infarction are more common in STEMI (34.8%) but can be found in patients with myopericarditis patients (5.9%)(P < 0.005). In myopericarditis, ST elevation in V4–V6, especially V5 (91.2% vs. 19.6%, P < 0.01), is much more commonly observed than STEMI. In lead aVR, ST-segment elevation may also be present in STEMI patients (10.9%) but not in those with myopericarditis. ST segment depression in lead aVR is more common in myopericarditis than in STEMI (41.6% vs. 13.0%, P <0.01). ST-segment depression in other leads (e.g., excluding aVR) is more common in STEMI patients (67.4%) but can also be found in 35.3% of myopericarditis patients (P < 0.01).

A variety of conditions or factors can cause pericarditis or myopericarditis: 1. Infectious causes: viral (e.g., Coxsackie, Epstein-Barr, HIV), bacterial (e.g., Tuberculosis, Staphylococci, Streptococci), fungal, and parasitic infections; 2. Non-infectious Causes: autoimmune or inflammatory diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, vasculitides), metabolic causes (uremia, hypothyroidism), trauma, neoplasm, drug-induced, and post-myocardial infarction, i.e., Dressler’s syndrome. Specific laboratory studies are necessary to confirm the etiologies of acute pericarditis, and treatment is tailored according to the exact underlying etiology, patient’s condition, and comorbidities.

*Benign early repolarization (BER), like acute pericarditis, is associated with concave ST elevation on ECG. However, essential differences can help distinguish between these conditions. In BER, the concave ST elevation is seen predominantly in the mid-to-left precordial leads (V2-5). There is a notching (fish hook pattern, especially in lead V4) or slurring at the J point. The T wave is usually slightly asymmetrical and concordant with the QRS complex. The ST elevation/T wave height ratio in V6 is <0.25. There is no reciprocal ST depression as seen in myocardial injury. Clinically, BER is not uncommonly seen in young, healthy patients under 50 years of age. It is generally considered a normal variant not indicative of underlying cardiac disease. However, it may carry a future risk of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (VF), referred to as early repolarization syndrome.** On the other hand, in acute pericarditis, P-R depression may be present alongside widespread concave ST elevation on ECG. The ST elevation/T wave ratio can be more than 25%. Clinically, it may be associated with viral infections, autoimmune diseases, or other underlying conditions. Patients with acute pericarditis often present with chest pain that worsens with inspiration and improves when leaning forward, like the present case.

**Early repolarization syndrome refers to individuals with an early repolarization ECG pattern who have also encountered ventricular arrhythmias, particularly polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and VF. Early repolarization syndrome is a genetic disorder resulting from “gain of function” of outward potassium current channels or “loss of function” of inward sodium or calcium channels. The resulting J-wave and J-point elevation on the ECG predisposes to polymorphic VT, which can degenerate into VF, causing sudden cardiac death. Therefore, some patients with this syndrome may require an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) for management.

Keywords:

acute pericarditis, early repolarization syndrome, myopericarditis, STEMI

(ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction)

UpToDate:

Myopericarditis

Acute pericarditis: Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Early repolarization

A 67-year-old woman experienced progressive dyspnea with PND and leg edema for two weeks. PMH was significant for chronic hypertension for 20 years.

A 65-year-old man was brought in with progressive edema of the left arm below the elbow level for two weeks. It was not “red and

An 83-year-old woman was transferred to Emergency Department (ED) from a local hospital because of a marked deterioration of general status while being treated with

If you have further questions or have interesting ECGs that you would like to share with us, please email me.

©Ruey J. Sung, All Rights Reserved. Designed By 青澄設計 Greencle Design.